It’s reproduced everywhere, from endless photos to gift shop trinkets but, asks William Cook, have we missed the meaning behind one of the world’s most famous works of art?

In the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, between the toilets and the gift shop, tourists are queueing up to take selfies in front of Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers. They don’t want a photo of the painting – they want a photo of themselves in front of it. They want to put it on Facebook and Instagram. They want their friends and followers to know that they were here.

Yet if you look a little closer, you realise this narcissistic cavalcade isn’t quite what it seems. This isn’t the real Sunflowers, it’s a plastic reproduction – the same size, the same colours but with bigger brushstrokes, so blind visitors can run their hands over it and see these sunflowers in their mind’s eye.

These sighted visitors don’t care that this Van Gogh is made of plastic. For them it scarcely matter what’s real and what’s unreal anymore. For them, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers has ceased to be a painting. It’s a prop for their tweets and Snapchat posts, a backdrop in the endless movie of their lives.

The real Sunflowers is tucked away in a quieter corner of this busy gallery. It’s the centrepiece of a new exhibition about Van Gogh’s most famous work. Van Gogh and the Sunflowers is a fascinating show, explaining how he came to create this iconic image. It’s a treat to see his Sunflowers in relative seclusion, away from most other sightseers (like me). But here’s the funny thing – today, I reckon I spent longer in front of the fake Sunflowers, watching those tourists taking selfies, than I spent looking at the real thing.

This paradox got me thinking: in our brave new virtual world, can a work of art become too famous – so famous that we can’t really see it anymore? I’ve seen reproductions of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers so many times – in books and magazines, on billboards, and now on the internet – that coming face to face with the genuine article is bound to feel like an anti-climax.

Sure, it’s not quite the same – no photo ever is – but the knowledge that in a few seconds I can summon up a reasonable resemblance of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (or any other masterpiece) on my smartphone is bound to detract from the impact of seeing it first-hand. Do those blind visitors, who’ve never seen Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, have a more vivid and meaningful experience when they come here to feel this plastic reproduction?

Mercifully, when I stand in front of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers – the real one, not the plastic one – I still feel a faint flicker. Yet the final irony is that the Van Gogh Museum’s Sunflowers is itself a reproduction – a copy Van Gogh made of a picture he’d painted a few months earlier. The original, painted from life, hangs in London’s National Gallery. And even that one in London wasn’t the first one, but the fourth in a series. He painted seven Sunflowers in all, and they ended up as far afield as Philadelphia and Tokyo. The story behind them is one of the most intriguing in the history of modern art.

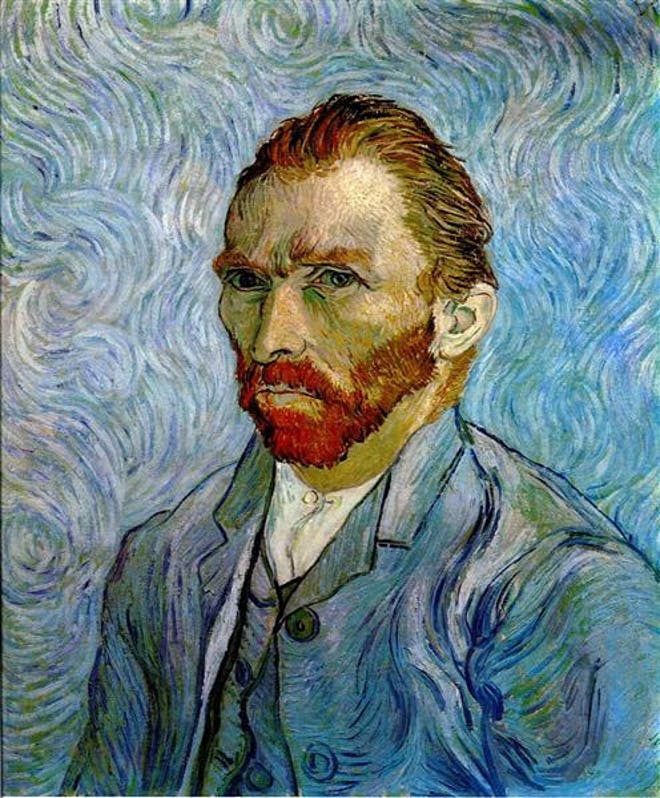

Van Gogh painted his first four Sunflower pictures in Arles, in the south of France, in August 1888. He was only 35, but he had less than two years to live. In February 1888 he had left Paris and travelled south, in search of warmth and light. He painted these sunflowers to welcome the artist Paul Gauguin to his home and studio – a house painted yellow, his favourite colour.

Van Gogh had met Gauguin in Paris 10 months earlier, when Van Gogh put on a small exhibition at a modest restaurant where he and his fellow artists hung out. He had not sold anything but Gauguin had seen the show and admired two small still lifes of cut sunflowers lying on a table, so Van Gogh gave them to him, in exchange for one of Gauguin’s landscapes of Martinique.

Gauguin was a struggling artist, like Van Gogh, but he’d had a bit more success so the Dutch painter was flattered by his interest in his work. When Van Gogh moved to Arles, he invited Gauguin to come and stay. He thought that living and working under the same roof, they’d spur each other on. Gauguin said he’d come but he didn’t say when. After six months, when Van Gogh painted his first four Sunflowers, his new friend still hadn’t set a date.

Van Gogh wrote to Gauguin to tell him he’d painted some sunflowers for his bedroom, hoping this might entice him. Sunflowers come from South America, where Gauguin spent his early childhood. They have strong religious associations – Christian and pagan. Did Van Gogh think the act of painting them might work some magic which would bring him south?

Gauguin finally arrived on 23 October. They made some wonderful paintings in this yellow house but they were both difficult to live with, the worst of housemates – it was never going to last. On 23 December, Van Gogh quarrelled violently with Gauguin, then cut off his left ear with a razor and delivered it to a local brothel. He almost bled to death.

It’d be harsh to pin the blame on Gauguin for this act of madness, but living with him surely helped to push Van Gogh over the edge. On Christmas Day Gauguin returned to Paris, leaving Van Gogh in hospital, on the brink of death. The two men corresponded thereafter, but they never met again.

Gauguin was a fickle friend, but he was a good judge of art. He had recognised the importance of Van Gogh’s Sunflower pictures straight away. He surmised – correctly – that they were among the best art Van Gogh had created. When he painted Van Gogh’s portrait in Arles, he portrayed him painting sunflowers, something he probably never saw him do first-hand. He called this portrait Le Peintre de Tournesols (The Painter of Sunflowers). Gauguin was the first to recognise sunflowers as Van Gogh’s defining motif.

When Van Gogh emerged from hospital, Gauguin wrote to asked him for one of these Sunflower paintings, but Van Gogh was loath to give away one of his greatest works to such a quarrelsome, inconstant friend. Instead, he made three copies – one of the third work in the quartet (aka Fourteen Sunflowers) and two of the fourth work (aka Fifteen Sunflowers). It seems at least one of these copies was originally intended for Gauguin, but Van Gogh had a change of heart and so Gauguin waited for his Sunflowers in vain.

Gauguin was not the only artist to recognise the significance of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers. In the spring of 1890, they were exhibited in Paris and Brussels, where they were praised by Monet but called “laughable” by an inferior artist called Henry de Groux. De Groux denounced Van Gogh as “an ignoramus and a charlatan”, whereupon Van Gogh’s friend, the diminutive Toulouse-Lautrec, challenged him to a duel. Despite his lack of sales, the word about Van Gogh was spreading. At last, it seemed his career was about to take off.

Van Gogh did not live to see it. On 27 July 1890 he shot himself in the chest. He died two days later, aged 37. Bursting with life and colour, the sunflower had become his calling card. “How could a man who loved flowers and light so much and portrayed them so well be so unhappy?” asked Monet. At the funeral, Van Gogh’s friend Dr Gachet brought sunflowers to adorn the coffin. Every year thereafter, he planted sunflowers on the artist’s grave.

The sunflower was soon established as Van Gogh’s trademark. The cover of the catalogue for his first retrospective in 1892 bore a drooping sunflower, encircled by a halo. The critics took the bait. Octave Mirbeau called Van Gogh a “beautiful human flower” who “understood the exquisite soul of flowers”, confirming that the worst writing is often inspired by the best art.

During the 20th century, Van Gogh’s seven sunflower paintings endured a variety of fates. His first sunflower painting (aka Three Sunflowers) ended up in private hands and has not been exhibited since 1948. His second sunflower painting (aka Six Sunflowers) was bought by a Japanese collector in 1920, and was destroyed in 1945 in an American bombing raid on Japan.

Thankfully, the other five are all on public view: Fourteen Sunflowers is in the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, Fifteen Sunflowers is in London’s National Gallery and Van Gogh’s copy of Fourteen Sunflowers is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. His two copies of Fifteen Sunflowers (signed and unsigned) are in Tokyo and in Amsterdam, at the Van Gogh Museum.

The unsigned copy of Fifteen Sunflowers travelled from Paris via Berlin and Dublin to London, where it was sold at Christie’s in 1987 for more than £25m – a world record. Conversely, the signed copy that is here in Amsterdam never left the Van Gogh family. Vincent left it to his brother Theo who left it to his widow Jo, who left it to their son Vincent Willem, who hung it in his home for decades before giving it to the Van Gogh Museum in 1973.

So what makes Van Gogh’s Sunflowers so important, so compelling? Why are we mesmerised by them? Is it simply because they’re amazing paintings? Or is it because we know they were made by someone who went mad and killed himself, having only ever sold a single painting? Are we transfixed by Van Gogh’s genius? Or are we merely obsessed with his celebrity?

Of course I’d like to say it’s the art alone that moves me, but like anyone who has grown up with Van Gogh, I cannot separate the artwork from the legend. I wish I could. Only someone who had never heard of him, who knew nothing about his life, or the market value of his paintings, could really appreciate his art for what it is, rather than what it represents.

In the museum gift shop they are doing a roaring trade in Sunflower merchandise: pens and pencils, playing cards and pencil cases, T-shirts and tank tops, socks and scarves, umbrellas and bandanas, salt and pepper shakers, aprons, mugs and oven gloves, badges, fridge magnets, even Christmas baubles. It’s all fairly harmless, I suppose, and it pays for lots of more important stuff, though I cannot help feeling it makes the actual art feel more remote than ever.

Yet there is still something about the Sunflowers which transcends the hype. Standing in front of it, some of the old magic survives. For me, what makes these works so special is that they’re the first Expressionistic still lifes, the first still lifes that convey what the artist really felt. No wonder Van Gogh was adopted by the German Expressionists as their forefather. Emil Nolde painted sunflowers too, but they weren’t a patch on Vincent van Gogh’s.

And it’s Van Gogh who deserves to have the last word regarding the endless reproductions of his paintings. Surprisingly, it sounds as if he would have been all for it. “No result of my work would be more agreeable to me than that ordinary working men should hang such prints in their rooms,” he declared, after the first lithographs of his work were produced in 1882.

What would he have made of Sunflower selfies and fridge magnets? Well, that’s anybody’s guess, but I have a hunch he would have liked them. History depicts him as a miserable bastard, but his life-affirming paintings suggest he was a lot more fun-loving than we might suppose.

Martin Bailey has written several books about Van Gogh, including The Sunflowers Are Mine, his riveting survey of Van Gogh’s sunflower paintings. He’s also curated several Van Gogh exhibitions. What he doesn’t know about Van Gogh is probably is not worth knowing.

“We think we know the sunflower paintings so well because we’ve seen them reproduced endlessly, and people don’t really look at them – but when you actually look at the painting you realise they’re at different stages,” Bailey tells me. As he points out, some of these flowers are in bud, some are in full bloom and some are already wilting. “Van Gogh is talking about the cycle of life. Everything blossoms and then dies, and then is reborn.”

Yet looking at Van Gogh’s Sunflowers with fresh eyes is becoming more and more difficult. “Now we’ve got images on our computer screens and iPhones and iPads we see endless reproductions of them, and our eyes tend to glaze over. We see it almost as a symbol of Van Gogh – it’s almost his logo, if you like – and we don’t actually look at it as a painting.”

Maybe it would be a good idea to have a moratorium on photographs of Van Gogh paintings, I suggest to him. Maybe that would help to get the freshness back? “I had this discussion with Moma [the Museum of Modern Art] in New York about Van Gogh’s Starry Night painting,” concurs Bailey. “Whenever you go there it’s surrounded by people with iPhones taking pictures. Moma allows photography everywhere. I suggested to Moma, ‘For half a dozen of the most important paintings in your museum, why don’t you ban photography in front of them?’ The curator I was speaking to said, ‘The public will get very annoyed.’ I said, ‘Well maybe it will make the public realise that these are very special pictures, and you should really look at them. They’re not just there to be photographed.’”

Yet the countless photographs of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers are central to their worldwide appeal. “There’s a sort of momentum that builds up, and once something becomes the artist’s iconic image it gets endlessly reproduced, and the fact that it’s reproduced more and more makes it even more popular.” The same could be said of Van Gogh.

“We have to accept the fact that people love Van Gogh’s work both because of the paintings themselves and because of the man behind them and the story behind them,” says Bailey. “It becomes very difficult to disentangle Van Gogh the man and Van Gogh the artist.” Yet Bailey doesn’t see this as such a bad thing. “If people come to his art because they are interested in his story, that’s fair enough.”

The Independent

Lebanese Ministry of Information

Lebanese Ministry of Information